by Robin McCloskey:

In 2014 adjunct faculty at San Francisco Bay Area universities began to advocate for labor justice. Instructors at Mills College, Saint Mary’s, San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI), California College of the Arts (CCA) and Dominican University, where I have been teaching for over a decade, all held union elections and within a few short months all had joined SEIU Local 1021. In the following year, faculty at Notre Dame de Namur and Holy Names College joined our ranks.

What motivated these campaigns?

Full-time, tenure track professors, the middle classof academia, have been slowly disappearing from our campuses over the last 40 years. In their place has emerged an army of gig workers, adjunct professors, who are poorly paid and usually have no benefits. Across America more than half of all faculty appointments are part-time, contingent faculty. At Dominican University at the time of our unionization, adjuncts comprised 75% of the faculty and taught half of all classes. These kinds of numbers are distressingly similar across the US. Many adjunct faculty work multiple jobs, commuting from campus to campus, trying to piece together a living wage.

I joined this movement in its early stages at Dominican University. I was motivated by my love of teaching and my conviction that current campus employment conditions are unfair to both students and faculty. I have remained committed to the cause, and served on the bargaining team that successfully negotiated our first contract that begins to address many of the inequities faced by our adjunct faculty.

Institutional change does not come easily, and throughout our organizing and bargaining we often needed to communicate our concerns to members of our university community and to the broader public. Art making played an important role in helping to spread our message.

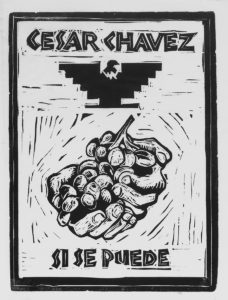

One of the first actions we held on campus was a public screenprinting event in front of our school cafeteria. We gave the prints away to anyone who was willing to take one, students, faculty and staff. It was encouraging when we began to see the posters mounted on bulletin boards and outside offices on campus. Later during that same school year, we held a relief-printing event on Cesar Chavez day. While many honor his memory, often forgotten is that he was a tireless advocate for unionization to address the plight of the farm workers. Our goal was to educate our community while honoring this giant of the labor movement.

On other campuses, innovative actions were taking place, particularly at SFAI and CCA. During one event at Fort Mason, the San Francisco Poster Syndicate provided hand-printed protest signs for marching adjuncts, while California Society of Printmakers member, long-time activist and SFAI adjunct Art Hazelwood and the Great Tortilla Conspiracy used chocolate syrup to screen print satirical images on edible quesadillas.

At CCA, Alisa Golden spearheaded a “bind-in” of handmade books whose pages detailed the personal struggles of contingent workers on campus. The power of converting spectator to participant – anyone willing to grab a needle and thread – was essential in this quiet but effective action. CCA adjunct Noga Wizansky describes the “pleasure of making” that the binders experienced. Noga reprised this project for participants at the Faculty Forward conference in Washington, DC in the summer of 2017.

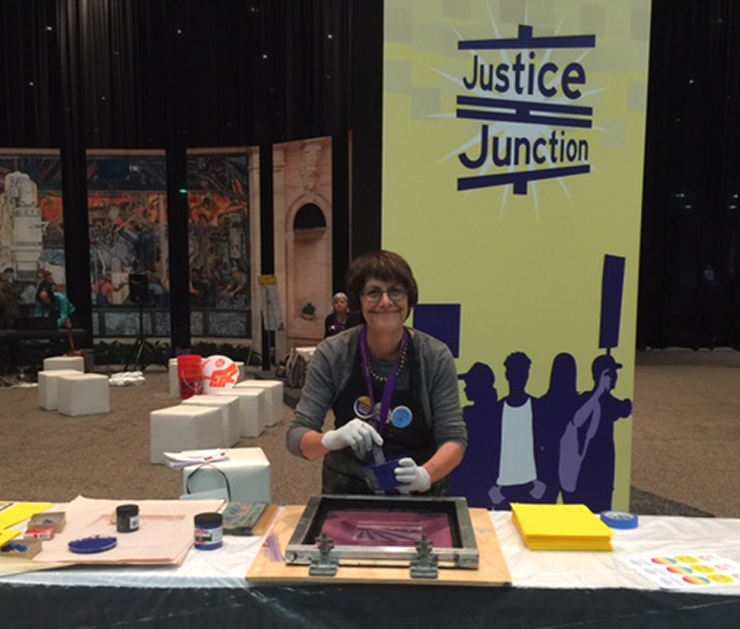

SEIU leaders took note of the potential of these creative art actions to inspire engagement and influence campaigns. A group of San Francisco Bay Area adjuncts was invited to collaborate in a multimedia art performance at the SEIU Unstoppable Convention in 2016 in Detroit. The performance included screenprinting posters (my role), chanting, poetry, a satirical skit where chocolate diplomas were awarded and a rousing, sing- along rendition of Solidarity Foreverthat closed the show.

This event was designed to encourage more creative approaches to activism and was well received by convention goers. We printed and gave away over 50 posters, and engaged with workers across a broad range of industries through performance and art making not typically a part of union activism. As one worker commented to me, “We usually hold signs and walk around in a circle.”

Part II

Recognizing the power of art to communicate and connect in the public sphere, questions remain for me about the relationship of aesthetics and activism or beauty and the struggle. The slow, layered, technical complexity that I seek in my personal work as a printmaker bears little consequence in the activist’s arena where one must make a point quickly and without ambiguity. As a studio artist I make prints that often take months to complete; prints for our public actions must be executed in a matter of hours or days. In my personal work, I print photopolymer plates augmented with thin veils of monotype color. The nature of this process makes it impractical in a public setting and unlikely to engage onlookers.

For our public print actions my work has been technically simple, visually bold and direct. These prints do not look or feel like “my work” to me even though I designed the images, fabricated the matrix and printed them myself. That doesn’t mean that these public printmaking experiences have not been richly rewarding. Having a large number of people possess something that I have made is immensely gratifying. While efforts in my studio result in small editions finding their way into a few hands, in the activist world we can place scores of prints with an audience for whom owning any kind of art may be a new experience.

Throughout my involvement in the labor movement I have grappled with these questions: Should I attempt to somehow synthesize my private studio imagery with my public printmaking? Would it be more ethical to abandon pursuit of the lyrical and poetic in favor of the direct and polemic? Is my work as an artist or activist somehow flawed if I cannot bridge this divide? I worry that my political prints are not rich or complex enough and that my studio work may lack relevance.

Though my work as a studio artist and an activist remains disconcertingly disconnected, I believe that there may be more bifurcation in artists’ work than is readily apparent. Visiting the recent Magritte exhibition at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art I wondered how much work is redacted from what we think of as an artist’s oeuvre? Significant exhibition space was dedicated to Magritte’s little known period ofsunshine surrealism, brushy and bright like a Renoir, complicating the Magritte I thought I knew. Hannah Hoch, now studied for her Dada collage work challenging notions of gender and body image, once proudly designed embroidery patterns for women’s hobby publications. Although Francisco Goya painted portraits of Spanish royalty, later in life he was to create prints intensely political and blisteringly critical of those in power. The imagery in his folio The Disasters of Waris so violent, disturbing and subversive that the editions could not be published until after his death.

In our current political climate, as in Goya’s time, it is imperative that artists speak out. Work that aims to challenge, provoke and agitate is indispensible for public action. In this era when the very foundation of our democracy is shaking, does the urgency for images designed for public action supplant the necessity of art that aims to provide a vehicle for quiet contemplation? Is it more useful to scream, chant and wave our signs or to dream, play and whisper our innermost feelings?

Fellow adjunct, artist and activist Noga Wizansky offers, “We don’t need to speak in just one mode. We can use our visual capacities differently depending on context.” In a recent New York Times feature on David Wojnarowicz (1954-1992), a multi-disciplinary artist and activist whose work challenged the indifference of the powerful in the face of the AIDS epidemic, fellow artist Zoe Leonard confesses to Wojnarowicz that she fears her photographs might be too preoccupied with beauty. Wojnarowicz said to her, “These are so beautiful, and that’s what we’re fighting for. We’re being angry and complaining because we have to, but where we want to go is back to beauty. If you let go of that, we don’t have anywhere to go.”

Robin McCloskey

October 2018